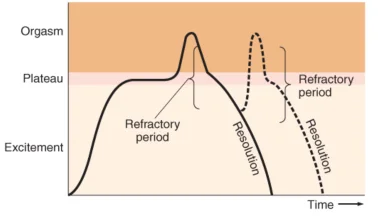

Basson's Sexual Response Cycle Model

Motivations. Motivations to have sex are quite diverse. In fact, one study discovered 237 unique motivations to have sex. They include things that you'd expect like emotional intimacy, physical pleasure, to express love, and attraction. Less frequently experienced motivations are to punish oneself, as an exchange for something, and to hurt someone. Motivations can be divided into approach motivations and avoidance motivations. Approach motivations are those that focus on something positive (e.g., pleasure, intimacy). Avoidance motivations are characterized by a desire to stop or prevent something (e.g., to stop a partner from leaving the relationship, fear of not being loved).

Sexual Stimuli. Certain stimuli will turn you on or increases your interest in having sex. Perhaps a kiss, or certain type of touch from your partner that says Let's get it on! Maybe it's seeing your partner naked. It could even be a smell or a sound. This is what initiates sexual arousal should all other conditions be met - like throwing a lit match into a pile of dry kindling.

Context and Mind. This may be the most important part of the cycle. Context refers to the current situation or environment in which sex could happen. The predominant context is your relationship. So, for example, a relationship characterized by trust, emotional connection, and flirty playfulness is much more likely going to increase strength of sexual response as opposed to a relationship that is in turmoil, with evident resentment, contempt, and conflict. Mind includes all your inner psychological processes such as emotions, thoughts, beliefs, and schemas. If you are feeling calm, confident, hot, and secure, you're going to be much more likely to become aroused and desire sex than if you're feeling anxious, unattractive, distracted, or unsafe. Your sexual scripts (i.e., what you think sex looks like) will also have an impact. If you have a particularly negative views about sex, you're probably less likely to be open to sex, particularly if it deviates from the type of sexual behaviour that you feel is appropriate.

Sexual Arousal. Sexual arousal typically occurs if there is motivation, sufficient sexual stimuli, and context and mind are good to go. Sexual arousal can be physiological (e.g., erection, vaginal lubrication, etc.) and/or psychological (e.g., feeling sexually aroused, horny, turned on, etc.).

Responsive Desire. Not all sexual encounters begin with spontaneous sexual desire. You have likely had many of these experiences, especially if you've been in a long-term relationship. The most common of these experiences is being approached by a partner who initiates when you haven't been thinking about, or desiring sex. However, you find yourself quickly getting in the mood - that's responsive sexual desire.

Satisfaction. A rewarding sexual experience, as you define it (which may or may not involve orgasm), will lead you to want more in the future. This is true about pretty much all of our experiences. On the other hand, a pattern of negative experiences may decrease your interest in sex in the future.

Spontaneous Sexual Desire. Spontaneous sexual desire can super-charge the sexual response cycle. It is that sense of sexual urgency, passion, or horniness that you've likely experienced. It can feed into the model at several points, and is particularly evident at the beginning of relationships during the honeymoon phase when sex is frequent. But, spontaneous sexual desire is not necessary to become aroused and have awesome sex. Responsive sexual desire can be as powerful a force.

Why It Matters

Significant problems at any stage of the sexual response cycle can lead to sexual difficulties and dysfunctions.

- Avoidance motivations are related to, and increase, anxiety and negative emotions that may hinder interest in sex and arousal.

- Insufficient or inappropriate sexual stimuli, such as partner who does not touch or stimulate you in a way that turns you on, will be a barrier to becoming aroused.

- A troubled relationship or negative emotions, thoughts, or schemas will typically stop the cycle from progressing.

- Unsatisfying, unpleasant, painful, or traumatic sexual experiences will decrease motivation to have sex in the future.

When these types of problems are adequately addressed, your sexual experiences will improve substantially.

Some Questions to Ask Yourself

What are your motivations to have sex? Are they approach motivations, or avoidance motivations? Are your motivations helpful or unhelpful?

How do your motivations affect your desire and arousal?

What sort of thoughts and feelings arise when you think about having sex? Are you anxious, fearful, uncomfortable, etc.? Or calm, confident, and secure?

Is there appropriate and sufficient stimuli to get you aroused (e.g., your partner's touch and stimulation, cues, etc.)? If not, what do you need and how do you get it?

If you're in a relationship, are you experiencing relationship problems that are impacting your desire for sex and your ability to be aroused (e.g., conflict, resentment, anger, etc.)? If so, what needs to change?

Have you had positive sexual experiences that increase your desire to have sex in the future? Or have they been mostly negative? If so, how can you increase the frequency of positive experiences and reduce those that are negative?

References

Basson, R. (2001). The female sexual response: A different model. Journal of Sex and Marital Therapy, 26(1). 51-65. (link)

Masters, W. H., & Johnson, V. E. (1966). Human Sexual Response. Toronto, New York: Bantam Books.

Meston, C. M., & Buss, D. M. (2007). Why humans have sex. Archives of Sexual Behaviour, 36(4), 477-507. (link)